Article from Die Gfänner, January, 2013

I want to thank Quartierverein Gfenn for the article and for the wonderful idea expressed at the end that people in Gfenn form a group to translate the novel so people who would actually be interested in it could read it! To that end, I'll study harder. For my English speaking friends, here's the translation and the article:

"Do you know Martha Ann Kennedy? Now, fascinated by the history of Switzerland and in particular that of the Lazarite, at San Diego State University instructive ended U.S. citizen is the author of Martin of Dübendorf.

The 13th-Resettled century historical novel tells the story of the foundling Martin, who grows up in a convent, and there learned the Zurich painting. Early on, he contracted leprosy, but it can before it forces them to take in, which serves as home for lepers Lzariterkloster refuge in Zurich as an artist to earn his bread. The imminent death before his eyes, he is devoting all his waning powers to create the ornamental church murals.

Martha Kennedy was supported in her research for the work of the historian Rainer Hugener. Accordingly, the novel on many details that reflect the reality at that time most exactly and provide an insight into the living conditions at the time. This is certainly interesting especially for Gfennerinnen and Gfenner.

Unfortunately, the book is so far available only in English and only in the online bookstore. Of course, the author wishes that the book one day in a German translation appears and rests in Swiss bookshop, but the moment is still the future.

Perhaps forms themselves a Gfenner translation group to train the novel one greater audience."

Amerikanerin Verliebte Sich in Lazariterkirche

"American Falls in Love with the Lazarite Church"

Martha Kennedy vor der Lazariterkirche im Gfenn: Die Fakten über das Leben in und um Zürich im 13. Jahrhundert hat sie in zeitintensiver Suche recherchiert. (Bild: zvg)

Teilen und kommentieren

Korrektur-Hinweis

Melden Sie uns sachliche oder formale Fehler.

Die US-Autorin Martha Kennedy ist fasziniert von der Gfenner Lazariterkirche, die sie während eines Besuchs in Dübendorf entdeckte. Als sie das Bauwerk das erste Mal betrat, sah sie den Stoff für eine Erzählung förmlich vor sich ausgebreitet. Derart inspiriert, legt Kennedy nun ihren Roman «Martin of Gfenn» vor. Dieser handelt vom leprakranken Künstler Martin, der, dem Sterben nahe, an den Wandmalereien arbeitet, die heute das Kircheninnere zieren. Um den historischen Rahmen der fiktiven Handlung exakt schildern zu können, liess sich Kennedy von einem lokalen Historiker beraten.

Lesen Sie mehr dazu im ZO/AvU vom Samstag, 12. Januar.

http://www.zol.ch/bezirk-uster/duebendorf/Amerikanerin-verliebte-sich-in-Lazariterkirche/story/20300920

Glattaler Interview, Gfenn Set Among the Palms, 10/26/2012

Gfenn Set Among the Palms

by Manuela Moser,

Glattaler, Friday, October 26, 2012

You live in California, in the mountains east of San Diego, and have written a book about a tiny chapel (Lazariterkirche im Gfenn) in Gfenn, a almost unknown place in Switzerland. How come?

I know that does sound sort of crazy, but when I visited the chapel for the first time I found it very beautiful. Reading about it in the brochure, I was stunned by its history. That experience planted the seed of inspiration and curiosity.

You once said the visit to Gfenn has changed your life. How come?

I have always been a writer, but I didn’t have a story. When I walked through the doors of the Lazariterkirche, I walked into my story.

Who is the main character, Martin of Gfenn?

Martin is a young painter who grew up in the Augustine Canons of St. Martin, contracted leprosy somehow, and ends up at Gfenn. He’s imaginary, though it’s not impossible that a person like him existed.

How did you have the idea for the story?

The story told itself to me. When I first visited the Lazariterkirche, I was impressed by the paintings, particularly the paintings around the window and the fragment on the wall of Christ being scourged. I imagined the artist and how he would be surprised to see his paintings there now. I began to wonder; what if he had been a leper artist, who’d lost every possibility to paint in the big world, and ended up painting murals in a leper church?

Is it a true story? The story is fiction.

The historical details are very accurate? How come?

I cared very much that the story be credible to Swiss people which meant I had to learn about the 1200’s. I grew up in the US and we have no “medieval past.” What we might have brought with us as immigrants is minimal. I had to become a medievalist historian to write the novel.

In the meantime, I was not the only person in the world examining and studying such things as leprosy in the middle ages. That was fortunate for me because, as I was putting together the puzzle pieces of the life of a medieval leper, scientists were reaching conclusions similar to those I was reaching by studying the literature of the time.

I could draw a fairly accurate general view of Zürich in the 1200’s, but at a certain point I became worried about details. That was when I contacted Rainer Hugener. I learned so much from him, many interesting details that I could not have found on my own, such as where in the city of Zürich the very poor would have lived at the time and the existence of the cloister in which I have Martin grow up. Mr. Hugener also validated the conjectures I’d made on my own. I reached a point where I felt that I was inept and failing. I expressed this to Rainer Hugener when we met and he said, “No. You just reached the end. We do not have much to go on from that time.” I was very insecure about my research because this was not my “field of study” -- though now it might be.

Did you undertake a lot of research?

I did -- I read everything I could find on the 1200‘s, discussions of the basic values of people in the middle ages before the 1300’s, as well as the works of St. Augustine and everything available on the attitude toward lepers at the time. I had to learn about the conventions of the Catholic church in the 1200’s, what the mass was at the time, how the Knights of St. Lazarus were organized and operated throughout Europe. I had to read everything I could find -- and I prefer reading primary texts when possible -- that had been written about lepers, leprosy and treatment in the 1200’s. It pushed my language abilities as far as they can go -- I can read French and Latin adequately (not great) but German, no. Of course, all the important religious texts of the time have been translated into English and I benefited a great deal from the fact that medieval people traveled, shared a common language for business and with certain important cultural variations, the Church and the military orders together created a certain homogeneity. Studies of the organization of a Lazarite compound in England would tell me something about one in Zürich. My research opened a beautiful strange world to me and I loved it.

When I visited Zürich in 2005, Mr. Hugener suggested I visit the Ritterhaus in Bubikon and I had a wonderful experience there, a private tour of a community that would not have been very different from Martin’s.

I studied medieval fresco and even went to LA to a four day workshop on fresco painting -- and painted a fresco. I spent a month in Verona studying Italian and pre-renaissance frescoes (Martin’s teacher is from Verona) and learned of Cennino Cennini’s work, The Craftsman’s Handbook which is a guide for artists written in the 1400’s, still, it gives very detailed instructions for making pigments, painting on plaster and so on that could have been true for the 1200’s. Again, in the meantime, science has made it possible to accurately determine the chemical composition and history of pigments used on very old frescoes, and because I had to stop working on the novel and return to it three years later, I was able to take advantage of that research, too.

Can you find a lot of information about Gfenn?

There is not a lot of information about Gfenn. Fortunately I was able to find Rainer Hugener who is certainly the world expert on Gfenn. :)

Are you yourself religious? Do you believe in God (big question!)

I am not religious, that is, I don’t go to church, and I don’t subscribe to any organized religions. I was raised Protestant, and my family was historically “Reformed,” actual followers of Zwingli’s doctrine. My grandmother grew up in a “Reformed” community in Iowa and raised her children in that faith. Naturally, I grew up believing that the Catholic church was evil. While writing Martin of Gfenn, I went to my first mass (I’ve now been to three -- once in Milan, in the Basilica of St. Ambrose to honor St. Augustine). I really loved the masses I have attended.

I believe there is beauty and truth in all religions, but my personal faith is probably best described as Pantheist. In my novel, Martin attends “my” church during the time he lives on the Zürichberg. It is the religion of, “Wow.” I believe the creative impulse in humans is a manifestation of the divine nature of the universe, so, when Martin paints the chapel at Gfenn, he is, in truth, at prayer. In old English “God” and “Good” are the same word. That works for me. I believe that kindness is the best “religion.”

And why is this chapel also for you so sacred?

On my first visit, I was enchanted by the window which makes the body of Christ and it plays a major part in my novel. It was a beautiful symbol to me since Christ represents the “...light of the world,” his compassion a window through which humanity can find hope, a light in the darkness. I was also moved by the persistence of the chapel itself, and the persistence of the paintings, through all the changes the building has seen and endured. I felt almost as if it were waiting for me, across all the centuries, to tell me a story. In a way, Martin is the chapel.

What is Lepra a metaphor for? What touches you about it most?

Leprosy is a metaphor for life. In the 1200’s the perception of a leper was somewhat complicated, but generally a leper provided the opportunity for others to demonstrate compassion.

It was also generally believed that we are all lepers in the sense that our souls are diseased and in need of healing, redemption, which can come only through the compassion of Christ. For medieval people objective reality (where we live) was less “real” than the spiritual reality. Objective reality was a flawed version of divine reality, and our lives but an allegorical representation of the MORE real (the spiritual reality). For them, leprosy was a metaphor for the general sickness of the soul. All humans were lepers and the person who had leprosy was just a little closer to God having the opportunity to begin the purgation of sin before death. This doesn’t mean that people didn’t fear lepers, but not with the terror with which they were portrayed in literature in succeeding centuries. I think it’s the same for us now, though our world view is different. Every one of us is challenged to fulfill our potential and realize our dreams. Thousands of obstacles and doubts jump in our way, we lose faith, we lose heart, we have periods of darkness and despair, we lose loved ones, we doubt, we become ill, we hurt others, we are repudiated by some, loved by others -- everything. I believe that what “saves” us is the same thing that “saves” Martin, and that is our human will to realize ourselves, faith in beauty and goodness, the will to be who we are, the willingness to share what little bit of something we have, to offer and accept forgiveness, to put our painting on the wall of our moment.

Who is your audience, who could be interested in the book?

I think the book should reach a general audience. It’s not difficult to read, and though some of the ideas are fairly abstract and it does have a religious theme, it’s not at all dogmatic. I imagine there are two things about it that could turn readers off. One is its religious theme (though Martin isn’t particularly religious nor is the book’s message) and the other is that it isn’t a “happy” story in the normal sense of happy.

What, if someone speaks not English and wants to read your book. Is there a German copy available?

There is no German version of Martin of Gfenn. It has been out less than a year, so I’m not sure anyone who has the ability to do that kind of translation has read it. It would make me very happy to see the book in German.

The “Glattaler” has portrayed you already in 2005. How come?

In 2005 I met Rainer Hugener online. I wanted to find someone who could help me verify the historical facts of my book. I actually “Googled” “Swiss medievalist historians, Zürich” or something like that. I found Mr. Hugener. We began corresponding and I emailed him the novel. We corresponded a lot, and I decided to spend my Spring Break in Zürich so we could meet. He was writing for the Glattaller at the time and the “interview” was, for me, a very wonderful day wandering in “Martin’s” world. Just like you, Manuela, he found it kind of amazing that someone in California would write about such a small spot on the Swiss map. His article is an interview, but also a record of what we talked about that day. It looked then that the novel would be coming out within the next year. It didn’t.

It was written there, the book would come out in the following year. Finally it appeared in 2011. How come the delay?

Life is full of surprises. In 2004/05, I had a contract with an agent in New York. In September 2005, I realized she was not going to do anything with the novel, and that I needed to find someone else. By November 2005 I was in tremendous physical pain which turned out to be advanced osteoarthritis in my hip. I’d always been an extremely active person, and it appeared that some forgotten injury years earlier had knocked my hip slightly out of alignment. Over the years, my hip had worn out.

I was no longer thinking of writing or anything other earning a living and finding a solution to the terrible pain I was in. It reached the point where I could barely walk. I’d been told by my doctor to have my hip replaced, and was exploring the consequences of that. It seemed to mean I would not be able to run or hike again. A friend of mine in Italy, who’s a climber and a doctor, suggested I have hip resurfacing rather than a hip replacement so I could continue running. In January 2007, I was able to have the surgery. Then followed the period of rehab.

It was not until 2009 that I was able to look at my novel again and see what it needed. I was not the same person, and I saw my novel with new eyes. I didn’t want to abandon Martin (because I really love “him” and I don’t believe he would ever have abandoned me) but the novel needed to be much better than it was. I spent two years intensively editing it and strengthening the prose. For the novel, the four year hiatus was good.

When have you been in Switzerland the last time? Do you plan to come back soon?

The last time I was in Switzerland was March 2005. I want very much to return, and I’ve looked at the possibility of either coming over during my winter break or at the end of school in May.

Why do you not promote your book in Zürich/Switzerland a little more? Why do you not read in Gfenn?

This has been on my mind since you first contacted me, Manuela, and asked about that. It would mean a great deal to me to read from my book at Gfenn. I am right now trying to figure out how. Although Swiss bookstores have Martin of Gfenn. available online, I don’t think any of them stock the actual book. I’ve contacted the English book buyer at Orell Füssli and sent a copy of Martin of Gfenn. as a start in that direction.

Do you plan a sequel of the novel?

I have written a “prequel” to Martin of Gfenn. It tells the story of the Commander of Gfenn when he was a young man. It’s a very strong, fast-moving novel, somewhat shorter than Martin of Gfenn.

by Manuela Moser,

Glattaler, Friday, October 26, 2012

You live in California, in the mountains east of San Diego, and have written a book about a tiny chapel (Lazariterkirche im Gfenn) in Gfenn, a almost unknown place in Switzerland. How come?

I know that does sound sort of crazy, but when I visited the chapel for the first time I found it very beautiful. Reading about it in the brochure, I was stunned by its history. That experience planted the seed of inspiration and curiosity.

You once said the visit to Gfenn has changed your life. How come?

I have always been a writer, but I didn’t have a story. When I walked through the doors of the Lazariterkirche, I walked into my story.

Who is the main character, Martin of Gfenn?

Martin is a young painter who grew up in the Augustine Canons of St. Martin, contracted leprosy somehow, and ends up at Gfenn. He’s imaginary, though it’s not impossible that a person like him existed.

How did you have the idea for the story?

The story told itself to me. When I first visited the Lazariterkirche, I was impressed by the paintings, particularly the paintings around the window and the fragment on the wall of Christ being scourged. I imagined the artist and how he would be surprised to see his paintings there now. I began to wonder; what if he had been a leper artist, who’d lost every possibility to paint in the big world, and ended up painting murals in a leper church?

Is it a true story? The story is fiction.

The historical details are very accurate? How come?

I cared very much that the story be credible to Swiss people which meant I had to learn about the 1200’s. I grew up in the US and we have no “medieval past.” What we might have brought with us as immigrants is minimal. I had to become a medievalist historian to write the novel.

In the meantime, I was not the only person in the world examining and studying such things as leprosy in the middle ages. That was fortunate for me because, as I was putting together the puzzle pieces of the life of a medieval leper, scientists were reaching conclusions similar to those I was reaching by studying the literature of the time.

I could draw a fairly accurate general view of Zürich in the 1200’s, but at a certain point I became worried about details. That was when I contacted Rainer Hugener. I learned so much from him, many interesting details that I could not have found on my own, such as where in the city of Zürich the very poor would have lived at the time and the existence of the cloister in which I have Martin grow up. Mr. Hugener also validated the conjectures I’d made on my own. I reached a point where I felt that I was inept and failing. I expressed this to Rainer Hugener when we met and he said, “No. You just reached the end. We do not have much to go on from that time.” I was very insecure about my research because this was not my “field of study” -- though now it might be.

Did you undertake a lot of research?

I did -- I read everything I could find on the 1200‘s, discussions of the basic values of people in the middle ages before the 1300’s, as well as the works of St. Augustine and everything available on the attitude toward lepers at the time. I had to learn about the conventions of the Catholic church in the 1200’s, what the mass was at the time, how the Knights of St. Lazarus were organized and operated throughout Europe. I had to read everything I could find -- and I prefer reading primary texts when possible -- that had been written about lepers, leprosy and treatment in the 1200’s. It pushed my language abilities as far as they can go -- I can read French and Latin adequately (not great) but German, no. Of course, all the important religious texts of the time have been translated into English and I benefited a great deal from the fact that medieval people traveled, shared a common language for business and with certain important cultural variations, the Church and the military orders together created a certain homogeneity. Studies of the organization of a Lazarite compound in England would tell me something about one in Zürich. My research opened a beautiful strange world to me and I loved it.

When I visited Zürich in 2005, Mr. Hugener suggested I visit the Ritterhaus in Bubikon and I had a wonderful experience there, a private tour of a community that would not have been very different from Martin’s.

I studied medieval fresco and even went to LA to a four day workshop on fresco painting -- and painted a fresco. I spent a month in Verona studying Italian and pre-renaissance frescoes (Martin’s teacher is from Verona) and learned of Cennino Cennini’s work, The Craftsman’s Handbook which is a guide for artists written in the 1400’s, still, it gives very detailed instructions for making pigments, painting on plaster and so on that could have been true for the 1200’s. Again, in the meantime, science has made it possible to accurately determine the chemical composition and history of pigments used on very old frescoes, and because I had to stop working on the novel and return to it three years later, I was able to take advantage of that research, too.

Can you find a lot of information about Gfenn?

There is not a lot of information about Gfenn. Fortunately I was able to find Rainer Hugener who is certainly the world expert on Gfenn. :)

Are you yourself religious? Do you believe in God (big question!)

I am not religious, that is, I don’t go to church, and I don’t subscribe to any organized religions. I was raised Protestant, and my family was historically “Reformed,” actual followers of Zwingli’s doctrine. My grandmother grew up in a “Reformed” community in Iowa and raised her children in that faith. Naturally, I grew up believing that the Catholic church was evil. While writing Martin of Gfenn, I went to my first mass (I’ve now been to three -- once in Milan, in the Basilica of St. Ambrose to honor St. Augustine). I really loved the masses I have attended.

I believe there is beauty and truth in all religions, but my personal faith is probably best described as Pantheist. In my novel, Martin attends “my” church during the time he lives on the Zürichberg. It is the religion of, “Wow.” I believe the creative impulse in humans is a manifestation of the divine nature of the universe, so, when Martin paints the chapel at Gfenn, he is, in truth, at prayer. In old English “God” and “Good” are the same word. That works for me. I believe that kindness is the best “religion.”

And why is this chapel also for you so sacred?

On my first visit, I was enchanted by the window which makes the body of Christ and it plays a major part in my novel. It was a beautiful symbol to me since Christ represents the “...light of the world,” his compassion a window through which humanity can find hope, a light in the darkness. I was also moved by the persistence of the chapel itself, and the persistence of the paintings, through all the changes the building has seen and endured. I felt almost as if it were waiting for me, across all the centuries, to tell me a story. In a way, Martin is the chapel.

What is Lepra a metaphor for? What touches you about it most?

Leprosy is a metaphor for life. In the 1200’s the perception of a leper was somewhat complicated, but generally a leper provided the opportunity for others to demonstrate compassion.

It was also generally believed that we are all lepers in the sense that our souls are diseased and in need of healing, redemption, which can come only through the compassion of Christ. For medieval people objective reality (where we live) was less “real” than the spiritual reality. Objective reality was a flawed version of divine reality, and our lives but an allegorical representation of the MORE real (the spiritual reality). For them, leprosy was a metaphor for the general sickness of the soul. All humans were lepers and the person who had leprosy was just a little closer to God having the opportunity to begin the purgation of sin before death. This doesn’t mean that people didn’t fear lepers, but not with the terror with which they were portrayed in literature in succeeding centuries. I think it’s the same for us now, though our world view is different. Every one of us is challenged to fulfill our potential and realize our dreams. Thousands of obstacles and doubts jump in our way, we lose faith, we lose heart, we have periods of darkness and despair, we lose loved ones, we doubt, we become ill, we hurt others, we are repudiated by some, loved by others -- everything. I believe that what “saves” us is the same thing that “saves” Martin, and that is our human will to realize ourselves, faith in beauty and goodness, the will to be who we are, the willingness to share what little bit of something we have, to offer and accept forgiveness, to put our painting on the wall of our moment.

Who is your audience, who could be interested in the book?

I think the book should reach a general audience. It’s not difficult to read, and though some of the ideas are fairly abstract and it does have a religious theme, it’s not at all dogmatic. I imagine there are two things about it that could turn readers off. One is its religious theme (though Martin isn’t particularly religious nor is the book’s message) and the other is that it isn’t a “happy” story in the normal sense of happy.

What, if someone speaks not English and wants to read your book. Is there a German copy available?

There is no German version of Martin of Gfenn. It has been out less than a year, so I’m not sure anyone who has the ability to do that kind of translation has read it. It would make me very happy to see the book in German.

The “Glattaler” has portrayed you already in 2005. How come?

In 2005 I met Rainer Hugener online. I wanted to find someone who could help me verify the historical facts of my book. I actually “Googled” “Swiss medievalist historians, Zürich” or something like that. I found Mr. Hugener. We began corresponding and I emailed him the novel. We corresponded a lot, and I decided to spend my Spring Break in Zürich so we could meet. He was writing for the Glattaller at the time and the “interview” was, for me, a very wonderful day wandering in “Martin’s” world. Just like you, Manuela, he found it kind of amazing that someone in California would write about such a small spot on the Swiss map. His article is an interview, but also a record of what we talked about that day. It looked then that the novel would be coming out within the next year. It didn’t.

It was written there, the book would come out in the following year. Finally it appeared in 2011. How come the delay?

Life is full of surprises. In 2004/05, I had a contract with an agent in New York. In September 2005, I realized she was not going to do anything with the novel, and that I needed to find someone else. By November 2005 I was in tremendous physical pain which turned out to be advanced osteoarthritis in my hip. I’d always been an extremely active person, and it appeared that some forgotten injury years earlier had knocked my hip slightly out of alignment. Over the years, my hip had worn out.

I was no longer thinking of writing or anything other earning a living and finding a solution to the terrible pain I was in. It reached the point where I could barely walk. I’d been told by my doctor to have my hip replaced, and was exploring the consequences of that. It seemed to mean I would not be able to run or hike again. A friend of mine in Italy, who’s a climber and a doctor, suggested I have hip resurfacing rather than a hip replacement so I could continue running. In January 2007, I was able to have the surgery. Then followed the period of rehab.

It was not until 2009 that I was able to look at my novel again and see what it needed. I was not the same person, and I saw my novel with new eyes. I didn’t want to abandon Martin (because I really love “him” and I don’t believe he would ever have abandoned me) but the novel needed to be much better than it was. I spent two years intensively editing it and strengthening the prose. For the novel, the four year hiatus was good.

When have you been in Switzerland the last time? Do you plan to come back soon?

The last time I was in Switzerland was March 2005. I want very much to return, and I’ve looked at the possibility of either coming over during my winter break or at the end of school in May.

Why do you not promote your book in Zürich/Switzerland a little more? Why do you not read in Gfenn?

This has been on my mind since you first contacted me, Manuela, and asked about that. It would mean a great deal to me to read from my book at Gfenn. I am right now trying to figure out how. Although Swiss bookstores have Martin of Gfenn. available online, I don’t think any of them stock the actual book. I’ve contacted the English book buyer at Orell Füssli and sent a copy of Martin of Gfenn. as a start in that direction.

Do you plan a sequel of the novel?

I have written a “prequel” to Martin of Gfenn. It tells the story of the Commander of Gfenn when he was a young man. It’s a very strong, fast-moving novel, somewhat shorter than Martin of Gfenn.

Readers Write about Martin of Gfenn

October 17, 1012, Martin of Gfenn gets fan mail!

"As a member of the book group that your friend ... is in please accept my thanks to you for the gift of your book, 'Martin of Gfenn.' I am currently reading it and engrossed by the beautiful, though sometimes horrific, descriptions. Your writing makes it so easy to feel Martin's heart. I greatly appreciate your generosity."

A conversation from Facebook, 6/1/2012

Martha Kennedy posts: Today a friend who is reading Martin of Gfenn said, "I don't get how a person as silly as you are wrote such a sad book."

"It's not sad."

"How is it not sad? This guy gets leprosy!"

"Yeah, so how is that sad?"

Must be me. ;-)

It seems to me that every life has sad stories. Sad stories don't make a life sad. I sometimes think back to AP English with the immortal Mrs. Zinn and learning about Greek tragedies and Aristotle's ideas that humans need catharsis, a consequence-less way to inspire pity and fear, and relieve the pressure of the pain of life. Art can help our lives be more bearable in the bad times by helping us see how great our lives really are. For example, who reads or sees Oedipus the King and doesn't think, "Wow. I'm so glad I never did MY mother and had to gouge MY eyes out. Now that's REALLY bad luck!"

So yes; I suppose Martin of Gfenn is a sad story, but still, I do not believe the protagonist is a sad man and that is the whole point.

Ginger Sickbert reponds: Martin finds his bliss... what he loves to do and can do excellently well; and he finds love in many ways. He develops strength of mind, enough so that he can counter the dogma of the religious around him... and yet can do it without being abusive or even uncivil. Wow. Seems like a pretty good life to me.

------------------------------------------

I have read this fable several times and find it is starting to live within me. I describe it as a fable because in spite of the scholarly work needed to present an understanding of the secular, religious and artistic life in 13th century Zurich and surroundings, it is primarily a picture of our human struggle to live, to love and to create while always aware of the brevity of life. Leprosy is the metaphor for this condition.

There is, of course, much sorrow here, but the sorrow is alleviated by the great beauty and clarity of the writing--especially in the many depictions of the beauty of the natural world and of the growth of love and understanding in the artist hero Martin. I highly recommend this book and look forward to reading more by Martha Kennedy, a terrific writer! Sarah Beynon, May, 2012

------------------------------------------

"Martin of Gfenn was an insightful novel of the human spiritual journey.

This well-crafted novel chronicles the 13th century artist, Martin, as

he struggles with perfecting his art, his understanding of God, and the

tragic disease of leprosy. Although Martin's story takes place almost

800 years ago, his journey is one that continues in humanity today. I

loved this novel and can't wait to read more from Martha Kennedy." Lois Maxwell, January, 2012

------------------------------------------

"Just finished Martin of Gfenn & I was moved by the poignant story & the quality of writing. Having seen gorgeous frescos in Italy & heard histories of the Catholic church's materialism & hypocrisy in terms of using & judging artists, I could relate these to the creative & spiritual dilemmas Martin became embroiled in." Ron Hueftle, November, 2011

------------------------------------------

"As a member of the book group that your friend ... is in please accept my thanks to you for the gift of your book, 'Martin of Gfenn.' I am currently reading it and engrossed by the beautiful, though sometimes horrific, descriptions. Your writing makes it so easy to feel Martin's heart. I greatly appreciate your generosity."

A conversation from Facebook, 6/1/2012

Martha Kennedy posts: Today a friend who is reading Martin of Gfenn said, "I don't get how a person as silly as you are wrote such a sad book."

"It's not sad."

"How is it not sad? This guy gets leprosy!"

"Yeah, so how is that sad?"

Must be me. ;-)

It seems to me that every life has sad stories. Sad stories don't make a life sad. I sometimes think back to AP English with the immortal Mrs. Zinn and learning about Greek tragedies and Aristotle's ideas that humans need catharsis, a consequence-less way to inspire pity and fear, and relieve the pressure of the pain of life. Art can help our lives be more bearable in the bad times by helping us see how great our lives really are. For example, who reads or sees Oedipus the King and doesn't think, "Wow. I'm so glad I never did MY mother and had to gouge MY eyes out. Now that's REALLY bad luck!"

So yes; I suppose Martin of Gfenn is a sad story, but still, I do not believe the protagonist is a sad man and that is the whole point.

Ginger Sickbert reponds: Martin finds his bliss... what he loves to do and can do excellently well; and he finds love in many ways. He develops strength of mind, enough so that he can counter the dogma of the religious around him... and yet can do it without being abusive or even uncivil. Wow. Seems like a pretty good life to me.

------------------------------------------

I have read this fable several times and find it is starting to live within me. I describe it as a fable because in spite of the scholarly work needed to present an understanding of the secular, religious and artistic life in 13th century Zurich and surroundings, it is primarily a picture of our human struggle to live, to love and to create while always aware of the brevity of life. Leprosy is the metaphor for this condition.

There is, of course, much sorrow here, but the sorrow is alleviated by the great beauty and clarity of the writing--especially in the many depictions of the beauty of the natural world and of the growth of love and understanding in the artist hero Martin. I highly recommend this book and look forward to reading more by Martha Kennedy, a terrific writer! Sarah Beynon, May, 2012

------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------

"Just finished Martin of Gfenn & I was moved by the poignant story & the quality of writing. Having seen gorgeous frescos in Italy & heard histories of the Catholic church's materialism & hypocrisy in terms of using & judging artists, I could relate these to the creative & spiritual dilemmas Martin became embroiled in." Ron Hueftle, November, 2011

------------------------------------------

"Thank you for the book. I'm reading it now. It's holding my interest and making me wish to return to it again...what a lot of research you must have had to do...am really so amazed at what a labor of love, skill, research and inspiration it is...Martha, I really liked it a lot. I finished it days ago and was sorry that it ended so soon, but I was greedy and didn't ration it. It is wonderful." Flame Schon, November, 2011

------------------------------------------

“Some

thoughts reading your chapters which are still very thrilling. We would

call it an artist novel about an artist whose work is growing more

perfect each day while he, himself, is increasingly decomposing from

leprosy -- a truly ingenious idea!” Rainer Hugener, Historian, Zurich, 2005

------------------------------------------

Reader: "I'm LOVING your book...how to you pronounce Gfenn? (G silent??) Anytime I think about a book even when I'm not actually reading it at the time, like on my hike today, I know it is making an impression on me." Nile Johnson

Martin of Gfenn: “Fen” -- and it means the same thing in English, marsh, swamp. Cool word, isn't it! ...and I'm very happy you like the book!

Here's a direct link to Martin of Gfenn on Lulu

"Lepra ist eine wunderbare Metapher"

This is a JPEG of an article written about Martin of Gfenn and published in a Swiss paper in 2005 after I went to Zurich to meet Rainer Hugener, a young Swiss Medievalist, who grew up in the very area where my novel is set. I found him online, introduced myself, he read my book (which at that time was twice as long and half as good) and loved it.

I decided to spend Spring Break in Zurich so I could really talk to Rainer and see everything again since I hadn't been in Zurich in 8 years. He met me at St. Peter's Church with a 13th century map of Zurich. The map was really a time machine! We went all around the old city, locating the places in my novel. I learned of St. Martins Augustine Canons Cloister on top of the Zurichberg -- long gone, nothing left but ruins and archeologists drawings. Rainer thought Martin should grow up there. We walked over the mountain (hill, large, large hill) down the other side, basically walking a route Martin walks in the novel, and we went to Gfenn on foot.

It was a truly great day. It ended with Rainer and his girlfriend, who made us fondue, champagne and tiramisu for dinner! That was when I learned that I am a "Swiss Medievalist Historian."

Rainer wrote this article for the local paper about my book and about my visit.

The opening is a translation of a section of the book (near the end). The rest of the article is about me, how I first came to Gfenn, how I became inspired to write and what I do for a job. It discusses the medieval view of leprosy -- which was, for the most part, NOT what we believe it to be. Leprosy was viewed by many as a blessing from God for two reasons. 1) It allowed others the chance to find salvation by showing compassion to the leper. 2) Since those who had leprosy were considered to be "dead" they were already on their way to Heaven, doing penance before they died.

I have two other novels -- one nearly finished -- that spin off this book. I joked around with Rainer about starting a "leper genre" and he has written about that in this piece.

The protagonist of my novel also likes bratwurst, which Rainer has mentioned in the article. On our time-travel jaunt around Zurich, we honored Martin's food preferences by stopping at the best place for bratwurst in Zurich, Sternen, where you can get a bratwurst, a roll, a beer or, (if you are me) a Rivella Rot.

We were joking around about how people might read the novel in the future and ascribe all kinds of symbolism to, uh, sausages. I said, "Well, sometimes a bratwurst is just a bratwurst!" and Rainer has used that line as a heading for a section in which he discusses the accuracy of my research. He writes about how I cannot really read German, but I managed to work out -- word by word -- the contents of many of the sources I used.

It was a great day -- and yesterday I was so happy to find this article (saved in an arcane folder of my computer) that I thought I had lost! If you click on the images, they will be large enough to read.

I decided to spend Spring Break in Zurich so I could really talk to Rainer and see everything again since I hadn't been in Zurich in 8 years. He met me at St. Peter's Church with a 13th century map of Zurich. The map was really a time machine! We went all around the old city, locating the places in my novel. I learned of St. Martins Augustine Canons Cloister on top of the Zurichberg -- long gone, nothing left but ruins and archeologists drawings. Rainer thought Martin should grow up there. We walked over the mountain (hill, large, large hill) down the other side, basically walking a route Martin walks in the novel, and we went to Gfenn on foot.

It was a truly great day. It ended with Rainer and his girlfriend, who made us fondue, champagne and tiramisu for dinner! That was when I learned that I am a "Swiss Medievalist Historian."

Rainer wrote this article for the local paper about my book and about my visit.

The opening is a translation of a section of the book (near the end). The rest of the article is about me, how I first came to Gfenn, how I became inspired to write and what I do for a job. It discusses the medieval view of leprosy -- which was, for the most part, NOT what we believe it to be. Leprosy was viewed by many as a blessing from God for two reasons. 1) It allowed others the chance to find salvation by showing compassion to the leper. 2) Since those who had leprosy were considered to be "dead" they were already on their way to Heaven, doing penance before they died.

I have two other novels -- one nearly finished -- that spin off this book. I joked around with Rainer about starting a "leper genre" and he has written about that in this piece.

The protagonist of my novel also likes bratwurst, which Rainer has mentioned in the article. On our time-travel jaunt around Zurich, we honored Martin's food preferences by stopping at the best place for bratwurst in Zurich, Sternen, where you can get a bratwurst, a roll, a beer or, (if you are me) a Rivella Rot.

We were joking around about how people might read the novel in the future and ascribe all kinds of symbolism to, uh, sausages. I said, "Well, sometimes a bratwurst is just a bratwurst!" and Rainer has used that line as a heading for a section in which he discusses the accuracy of my research. He writes about how I cannot really read German, but I managed to work out -- word by word -- the contents of many of the sources I used.

It was a great day -- and yesterday I was so happy to find this article (saved in an arcane folder of my computer) that I thought I had lost! If you click on the images, they will be large enough to read.

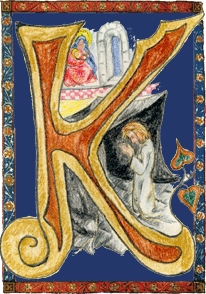

Series of Initial Letters I Drew for Martin of Gfenn

Book One -- St. Martins

|

| Draw the chickens! The feathers can wait! |

|

Book Two -- Zurich

|

| The city was a walled jewel between two blue strands of stream against a shining lake. |

|

“Don’t stop now!”

someone yelled. Making a grand gesture with his right arm, Martin slowly drew a

ladder. The people cheered.

“Good work, young man!”

said one old man in the crowd.

“I knew it was the story of Jacob!”

|

Martin saw only the girl

standing beside a chair waiting for her mother to be seated. Her brown hair was

parted in the middle, drawn back from her face and covered with the

lace-trimmed cap worn only by a maid. The pure whiteness of her skin was

interrupted only by pink roses on her cheeks, and when she lifted her face to

greet him he saw sweet blue eyes fringed with dark lashes above a friendly,

open smile. Her lips were the pure carmine Michele said had no place in nature,

and here it was, as natural as morning.

Book Three - The Sagentobel

| |

| “You may believe that you are Martin, an artist, but for some time you have been Martin, a leper. No man is whole until he is able to live as himself...” |

Book Four -- Gfenn

|

|

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)